Pontormo's Madonna with Child and Saints

Jacopo da Pontormo's Madonna with Child and Saints, oil on painting, 1518

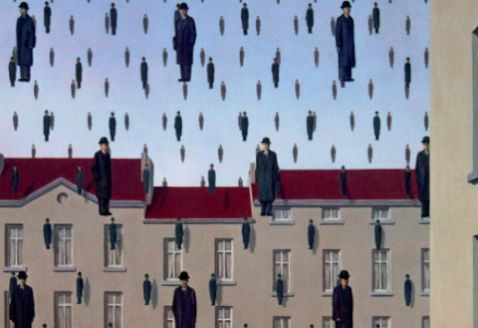

The piece I selected comes from the High Renaissance, or Late Renaissance, which began roughly around 1520 until about 1580. This peak period has been dubbed the Mannerist period. I immediately became interest in this particular style of Renaissance art due to the literal definition of mannerism: a habitual or characteristic manner, mode or way of doing something; a way of speaking or behaving; an idiosyncrasy.

The fascination I find in people from all walks in life is they are uniquely themselves--they have their own idiosyncrasies, their own peculiarities that naturally bring to light their individuality and being. So when we learned about the outgrowth of Mannerist artists from the Italian Renaissance, I was taken by this particular group that studied and contributed to a pivotal movement in the visual arts, and also made it their own. While the humanist philosophy jump started this movement in the Italian, then Northern Renaissance, with a central focus on the individual with accuracy and as nature intended, the mannerists seemed to play with this idea of natural look, and serenity that can be found leading up to the later stages of the Renaissance.

Pontormo was regarded as a religious painter, but even at one point was hired by the Medici family to paint mythological figures for their villa (Britannica, 2021). In Madonna with Child and Saints, the Virgin Mary sits above and is seen handing over baby Jesus to St. Joseph. They are surrounded by the Saints John, Francis, and James. What is noticed instantly in these oil painting is the dominating shadows which dominate the background and even in between unusually long figures. Bright skin quickly becomes engulfed in shadow, and faces look no where near where shoulders face. What stands out in this composition is the ratio of human flesh to negative space--there are far too many people in this painting. This is attributed to the Mannerist period as well, removed from the characteristic natural and tranquil settings which governed the Italian Renaissance.

After reading further about Pontormo, I felt the familiar sense of tragedy that hampered his life. At a young age, he had lost parents and a siblingI believe, in the span of a few years. In older age he was shuttered in, and lonesome. It's difficult or impossible to separate emotionality in such a work as this, which is why I greatly appreciated it. When I read about his background and saw he gradually took to the distorted and strange movement that was Mannerism later in his career, I couldn't really help but relate to or understand such a progression. That being said, I would certainly own such a piece of work.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Jacopo Da Pontormo | Biography, Art, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 May 2021, www.britannica.com/biography/Jacopo-da-Pontormo.

“Jacopo Da Pontormo Paintings, Bio, Ideas.” The Art Story, 4 Jan. 2021, www.theartstory.org/artist/pontormo-jacopo-da.

Knowing Jacopo Da Pontormo's past and how tragedy has colored his life it's easy to see why his pantings would come out darker. I find the mannerist movement interesting, there is a feeling of something about to happen but wasn't captured in the painting makes a very tense atmosphere. In this piece you can see multiple people looking in the same direction with expressions that are hard to read, but it doesn't seem to be something good.

ReplyDeleteThat is an interesting take on mannerism. I don't really like the style, but the way you describe it is pretty appealing -- although now that you mentioned the extreme head-turns, I can't unsee that. It somewhat feels like the viewer just walked into a surreptitious closet meeting and gets the indignant interruption stare. You are right that this painting depicts quite a crowd! Maybe this abundance of company, and the amount of detail given to the people vs the background, also relates to the artist's circumstances.

ReplyDelete